Today was not a good day for birds of peace, or so it seems at first glance. In a service at Saint Peter's, two children released doves alongside the Pope as symbols of hope and peace amid the turmoil in Ukraine. After their release, a

crow and then a seagullquickly attacked the birds. Though it appears the doves may have gotten away, social media outlets were quick to note that the sight was a "bad omen." This led me to think a bit about birds and divination, and to ruminate on whether this sight would have been viewed as negative in Roman antiquity.

On the day of April 21, 753 BCE, Rome was born. It was on that day that Romulus undertook the auspices--a bird watching--alongside his brother Remus. While Remus saw 6 vultures, Romulus saw 12. As

Plutarch notes, Romans tended to have a strong trust in vultures and it was indeed a rare sight to see one (Plut.Rom.9.6-7). Whereas vultures have a negative connotation today due to their scavenging (I personally blame the

Jungle Book), Romans did not have the same bias. I'd venture to guess that if a Roman and a modern American (or perhaps Canadian) both viewed vultures in the sky, each would have a different reading of the event.

![]() |

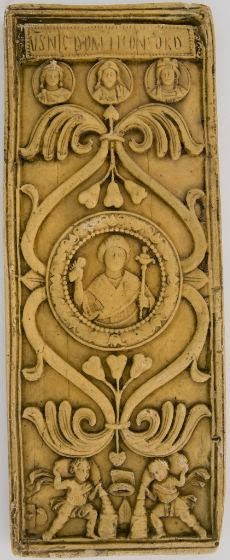

Marble altar dedicated to

Jupiter, the Sun, and Serapis

by a augur (3rd c. CE) |

In any case, Romulus was the clear victor in the brotherly competition, but when Remus came to believe that Romulus cheated, he was enraged. The subsequent brawl ended with Remus dead, possibly at the hands of his brother. Besides playing an integral part of Rome's foundation myth, the vulture viewing served to activate Rome's

auspicia publica, along with the ability to interpret the divine will of Jupiter. Although there are differing interpretations, Romulus appears to have appointed three augurs and then another king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, formally began the college of augurs (Liv. 4.4.2). In terms of its role in Roman religion, Cicero argued that the augurate was of the highest importance to the republic, though, as one would guess, he was also an augur himself.

![]() |

Reverse of a denarius of Sulla

with lituus and pot (84/3 BCE)

Münzkabinett der Staatlichen

Museen zu Berlin |

In terms of the taking of the auspices, usually, a

templum was drawn out in the sky by the augur with his special staff, a

lituus, and the sky marked off east to west, north and south. The augurs were concerned with signs

ex caelo (out of the sky) and

ex avibus (out of the birds). Thunder and lightning fell under the umbrella of

ex caelo, and were of the highest import to the state. The birds that fell within the second type included vultures, crows, ravens, owls, eagles, and hens, which themselves were divided into birds that sang their message and those that flew in order to transmit divine will. The auspices also came in two types, those directly sought by the augur,

impetrativa, or those simply dispersed by the gods,

oblativa. Popular assemblies and meetings of the senate needed favorable auspices, as did inaugurations of certain buildings and officials. Even weddings were preceded by the taking of the auspices. Planned auspices were only valid for a day and were usually taken between midnight and dawn.

![]() |

| Arian baptistry, Ravenna, Italy. |

Notably, according to these laws, this was one of the

oblativa signs, but the seagull and the doves flying at St. Peter's fall outside the normal birds interpreted by the augurs. Gulls and pigeons (sorry, doves) don't fall into this rubric and thus the only bird that matters in this scenario is likely the crow. If he flew to the left, this was auspicious, to the right, inauspicious (Cic.

Div. 1.39). If someone has some insight on what the pictures show, I'd love to hear it.

I wanted to take this opportunity not only to explore the College of Augurs, but to show how birds can change in meaning over time and culture. Me? I am going to choose to believe that the doves got away and that the crow is a sign that the upheavals in Ukraine will come to a peaceful resolution. Truth is, I am not an augur and neither are you. Constantius' edict of 357 CE (

CTh. 9.16.4) put an end to the College of Augurs and the last known augur,

Lucius Ragonius Venustus lived only into the 390s.